On Bob Matheny: (more or less)

by Dave Hampton

The following essay was originally written in 2018 in conjunction with Bob Matheny's receipt of the San Diego Art Prize. Updates were made in 2020 for this website.

Robert Earl "Bob" Matheny (b. Santa Ana, CA., 1929--d. Point Loma, CA., 2020) was a sculptor, painter, graphic designer, educator, small press operator, performer, and idea artist. He studied with art department chair John Olsen, Stan Hodge, and others at Long Beach State College (now known as California State University, Long Beach), and earned an MA in art education. In 1958 Matheny moved to San Diego to work as a graphic designer for Hodge, who was then manager of art direction at Convair Astronautics Division of General Dynamics. Like his good friend Jim Sundell, Matheny arrived through a talent pipeline from Long Beach State and City College art programs to San Diego defense contractors and military-industrial entities. Sundell worked under Barney Reid at the Navy Electronics Laboratory in Point Loma (where Matheny, Russell Baldwin and John Baldessari also briefly worked). Such postwar science and aerospace organizations employed many San Diego artists and were known for generating award-winning graphic design.

He worked in a variety of media, including fabricated metal jewelry and hooked rugs, and made a few pieces of furniture based on modernist designs by Knoll and Herman Miller. But by the late 1950s Matheny had developed an abiding fascination with typography and small press printing. In his hands these specialties reflected formal tenets of modernist design that shaped much of his work and remain a primary unifying theme of his diverse overall practice. (figure 1)

His first contributions to the greater San Diego art community were in the field of letterpress printing. Matheny organized a group of graphic design professionals called the Patrons of the Private Press with Bill Noonan, Rene Sheret and Burt Brockett, who met regularly to exchange and discuss their work, and in 1960 he arranged for an international exhibition of private letterpress printing at the San Diego Museum of Art.

(figure 2)

A few years later Matheny developed a signature series of Letter Form paintings and sculptures—freestanding words, individual letters, and punctuation marks carved out of wood on a band saw—some in smoothly finished hardwoods, others painted with glossy enamel in primary colors. There was also a series of limited edition Typograph prints involved literary quotations, composed with type and other printing ornaments and produced on a flat letterpress poster press. (figure 3; figure 4)

Matheny commuted for a time, teaching at Newport Harbor High School and Santa Monica City College, but in 1961 he became the first full-time art instructor at Southwestern College in Chula Vista (along with early part-time faculty members Dick Robinson and John Dewitt Clark). Once settled in this new position, where he remained for the next thirty years, Matheny produced what he considered his first "adult" works of sculpture and painting in 1963-64. Coming before his Letter Forms, these were early mixed-media hybrids such as Does God Bless the John Birch Society, a mock-patriotic tableaux of a seated tuba player—its absent figure suggested by a band member's shoes and hat, a real tuba, and partly real, partly painted chair. A timely example of West Coast Assemblage, Does God Bless the John Birch Society draws from Duchamp and Dada in the second major theme of Matheny's career, which extends to performances and situations captured on film or video. (figure 5)

Pail, a.k.a. Pails of Plaster (and paint), c. 1963, was another early work that embodies Matheny's unique twist on Duchamp's influences and the objet trouvé. This plaster casting taken from inside of a gallon bucket closely represents an everyday household object; Matheny even attached the handle from the original plastic bucket. It carries swirls of colorful pigment, however, that bring the idea of painting into play. Matheny's Pail was exhibited in group shows at both Southwestern College and San Diego State University in 1965, and reviews in Artforum as well as local publications singled out the work's conceptual and playful qualities. Before "conceptual art" became a commonplace term, Dr. Armin Kietzmann wrote in The San Diego Union that "theory," or "an idea or mental plan of the way to do something" was the "determining factor" in works such as Matheny's Pail, and in Artforum, Marilyn Hagberg described the sculpture as "good sport." (figure 6)

The idea is at play throughout Matheny's creative practice and his work frequently paralleled other life interests, from soaring gliders and flying small aircraft, to a deep reverence for the landscape of southern Utah and his legislative campaign to establish there an independent Great State of Art. Matheny created major bodies of work related to these ideas, combining post-studio art forms with more traditional disciplines. (figure 7; figure 8; figure 9)

He pursued an array of series including Infamous Babes, Chicks, Dames, Dolls and/or Statues of Liberty and Freedom, a collaboration with Armando Muñoz Garcia. Still-Lives Documented and Palettes with a capital P took on potentially hopeless art world clichés. Tobacciana and cigar band pseudo-histories were featured in Matheny's Hook 'Em Cow project, which was manifest as both an exhibition and a book. (figure 10)

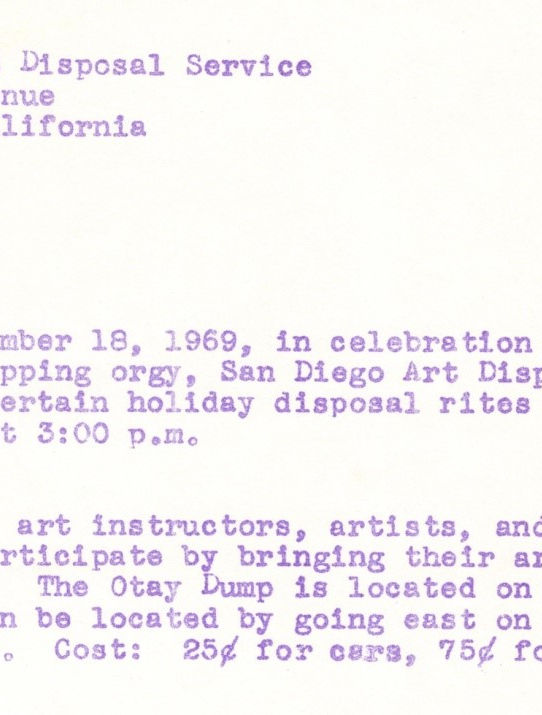

Good humor is at the forefront of his collaborative intermedia performances, which include operating the San Diego chapter of the Art Disposal Service. After signing a contract with the organization's Los Angeles headquarters in July of 1969, Matheny issued a press release (notices were subsequently published in the newspapers) and prepared for "holiday disposal rites" that December at the Otay dump. (figures 11,12, 13)

Matheny later recounted how a group of citizens arrived to protest -- members of a local art group provoked incensed by the idea of Art insensitively rendered into landfill. Students from Southwestern College contributed much of the material for disposal that day and, in solidarity with the protestors, one student dramatically prostrated himself in the path of an approaching bulldozer. Sculpture professor John DeWitt Clark also made labels to place on trash cans around the Southwestern campus, designated as official Art Disposal receptacles. Despite the uniquely personal ebullience that runs throughout Matheny's work, in what are arguably his best works, this playful impulse is tempered by "good design" principles instilled by his modernist teachers.

An obsessive object maker, craftsmanship is crucial in Matheny's most sublime works, which integrate concept and object in an especially distinctive way. In the 1966 sculpture titled Bomb 'Em, for example, Matheny carved the letters and apostrophe of the title phrase in walnut, further articulating the typeface with paint, to make an eye-pleasing series of geometric shapes. Bomb 'Em—its semantic content taken from a Vietnam War-era newspaper quotation, possibly USAF General Curtis Lemay's notorious "bomb 'em back to the stone age"—renders a horrifying notion with style and elegance, and sarcasm, to deliver an anti-war statement. (figures 14 & 15)

Matheny has long appreciated modern furniture design, which recently resulted in a set of tables made by Jason Lane to accommodate and display a suite of Matheny's paintings (or Squeezings). In addition to a coffee table with a geometric pattern of twelve squares cut into the top, there is an end table that supports a portable tower of twelve small paintings. Their sturdy frames must be lifted out of their stack one at a time, in a ritualized sequence like turning the pages of a book. But instead of a coffee-table book with photographs of paintings, twelve actual paintings can come out of the structure and fit into the tabletop. (figure 16; figure 17)

Matheny founded the Southwestern College Art Gallery in 1962, and was responsible for many years of robust exhibitions (the first, a one-man show by John Baldessari), a film series, art happenings, and activism over the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the school’s forward-thinking permanent collection of contemporary art. The remarkable impact of this out-of-the-way community college during the 1960s still reverberates, not only for the artists, students, and public who experienced it firsthand, but also for those who, in looking back, have begun to appreciate this city’s midcentury arts heritage. In February 1994, The San Diego Union-Tribune published Welton Jones' definitive article about the Southwestern College art phenomenon. It quotes John Baldessari (who taught there with Matheny during the late 1960s) as saying “… in retrospect, Southwestern College was very important, even though a lot of what we did was just spitting in the wind. And, if you had eliminated Matheny from the picture, none of that stuff would have happened.”

Since retiring from Southwestern in 1991, Matheny continues to baffle and provoke the local art community with a compelling stream of idiosyncrasies, including handing out two-dollar bills that he signed and rubber-stamped with the word "real." His 2016 public burial of a “real” Willem de Kooning painting in the inner courtyard of local arts complex Bread and Salt mesmerized the audience even as it recycled and interred his own art-historical legacy. The questionable canvas laid to rest was originally painted for an pseudo art "auction" featuring Dick Robinson as auctioneer and other art faculty and students in the early 1970s—a genuine counterfeit artifact of the Southwestern College art happenings. (figures 18-20)

Matheny remains ever-vital to San Diego's art community at almost 90; an inspiration as well as a living link to the city's art history. He told me recently that he's begun saving the proceeds when he sells an artwork and using that money specifically to buy works from artists he wants to support. Now, Bob's been exchanging art with other artists for at least 60 years, but he spoke as if this was something newly satisfying, a discovery that had just occurred to him. This kind of open-minded and perennially positive attitude is key to Matheny's character, given his decades of enduring the lack of opportunities and recognition for artists in San Diego. So let's hope this prize is just the beginning of the recognition that Matheny deserves. There should be a street named after him, or a building—perhaps a regional airport. Or a dedicated section of the landfill that can properly accommodate art objects.

Dave Hampton, 2018/20